81. Al Scates: You need to enjoy yourself.

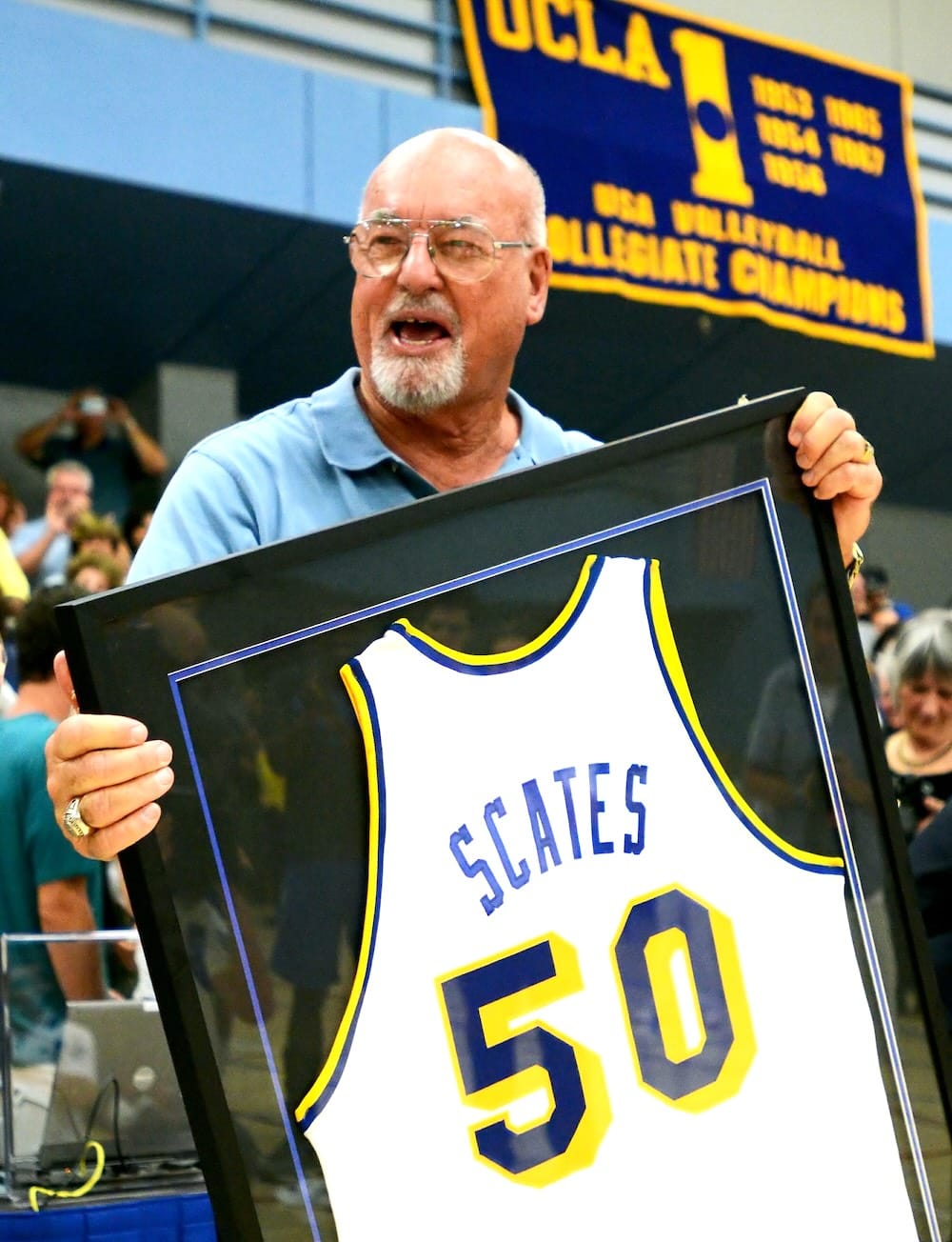

Welcome to our Masterclass Interview with Al Scates, a legendary figure in the world of volleyball. Al's remarkable career spans five decades, during which he transformed UCLA's men's volleyball team into a powerhouse.

Under his leadership, the team secured 19 NCAA championships, making him the winningest coach in NCAA history.

Under coach Scates, UCLA holds 27 NCAA men's volleyball team and individual records, including consecutive victories (48), consecutive home court victories (83), consecutive NCAA tournament victories (15) and most undefeated seasons (3). No other program boasts an undefeated season.

Through his program, Scates has coached 78 All-Americans, 44 U.S. national team members, 27 Olympians, 7 players that were chosen as NCAA Player of the Year, and launched dozens of coaching careers.

In this interview, Al shares:

- his unique approach to team preparation

- how he kept on focusing on the future

- how he sought after international play to enhance skills

- how he thinks about internal competition and player discipline

- how he was influenced by early coaches and mentors

- why we need to prioritize player well-being

- how he used losses as motivation for future wins

- and so much more...

We also dive into his favorite pastimes, including his love for golf and the camaraderie he shares with his friends and former players.

Enjoy this insightful interview with Mr. Al Scates.

Thank you for your time, Al.

Reflecting on your extensive coaching career, I've gathered insights from various online sources, particularly from former UCLA players who are now coaches themselves. These sources frequently highlight aspects of your coaching style, leading me to identify the "Al Scates' coaching fundamentals." These principles can seem universally acknowledged, yet perhaps their obvious nature makes them challenging to implement consistently.

With each fundamental, I have two questions. First, how did you, in your early days, come to understand these fundamentals? Secondly, for a novice coach, why would you emphasize the importance of adhering to these fundamentals?

To clarify with an example, many described your demeanor during practices and timeouts as calm and confident, occasionally marked by a reassuring laugh. Did this composure come naturally to you, or was it a trait you developed? Some coaches might struggle with maintaining their composure, what advice would you offer them?

In the beginning, I was still playing when I started coaching, so it was very difficult for me to coach without getting excited. In fact, I had problems—I was getting an ulcer. When I went to the UCLA hospital to get treated, I decided I was going to be very calm and take care of my blood pressure.

If I noticed my pulse rate was going up, I would calm myself down. It was easy to do if you just thought about what you were going to do next to combat whatever the opponent was going to do next.

By thinking ahead, I never worried about what happened in the past. I only focused on what we were going to do next.

So during the timeouts, which I took early after the opponent scored a couple of points, I would tell my team what we were going to do because the opponent was usually serving at that time. If I called the timeout, I told them what we were going to do and then how we were going to score on the next play, depending on the matchups, their rotation versus our rotation.

I told them two things: how we were going to win the side out or the next point in the modern game, and what they were going to do on a good pass. If I needed to change blockers, I told them all that. You only had a minute in the beginning, and then you had more time later depending on TV timeouts and stuff like that.

So I had a lot to tell them, and I didn’t have time to be excited if a player made a mistake. He knew that.

I didn’t dwell on that. I didn’t try to teach him anything or how to correct his error; that would have been a waste of time. If the opponent called a timeout, then based on what I knew about the team and the coach, I knew what he was going to tell his setter to do next, so I just focused on scoring. Of course, I told our server where I wanted him to serve the ball.

That’s how I stayed calm. I had a lot of information to get to the players, and if I didn’t know what I was doing, I felt unsure myself. I just looked confident. And since they believed me, whatever I told them generally worked anyway, even if it was the wrong thing.

You've already touched on why it's not good to show anxiety. Why waste your energy and shake up your players' confidence by looking nervous? It's better not to dwell on mistakes or scold players about what they shouldn't have done.

Absolutely, if a coach lacks confidence, the players will sense it, and it can cause stress and impact their own confidence.

Take, for instance, a game in 2006 against USC, which is just 12 miles from our campus. It was a televised match and a major one at that. We were behind and it came down to our last timeout.

The season really depended on this match because if we lost, we wouldn't make the league playoffs. At that time, they only took the top eight teams, and we were close to being the ninth. We had a strong record against other teams, but our league performance was weak.

It was a crucial timeout because the whole season depended on us winning this match. I did my best to appear very calm, which was a stretch because I wasn't. However, appearing calm was important.

We went on to win the next 16 matches in the NCAA championship. But if we had lost that match, we would have been out.

It's tough to appear calm, but most of the time I really was calm. However, you must appear confident to your team. It's very important.

Over your coaching timeline, it seems that adapting to changing standards, particularly those that evolve with each Olympic cycle, has been crucial. Volleyball rules have shifted over the years, and you've been notably quick to grasp these changes and consistently stay ahead of the curve.

Could you confirm if that's accurate? I'm interested in understanding how you've managed to continuously evolve your coaching strategies to maintain a competitive edge.

What I did was, we were dominating volleyball in the United States, so I needed to go to foreign countries because some of their teams were better than ours. I needed to play against national teams and strong teams from other countries, but I had no budget for it.

In the seventies, the Japanese were very strong. So, I went to Nippon Newspapers in Los Angeles and offered them exclusive rights to our trip to play Japanese teams if they would sponsor us. They agreed, and in 1979, I took my team to Japan. We played five matches there, and Nippon Newspapers covered all the expenses.

I had just become a full-time coach at UCLA the previous year, we could never cover those costs ourselves.

Experiencing the Japanese style of play, their speed, and their defense, I incorporated some of that into our program. The next year, USA Volleyball wanted me to coach a team for an international tournament in Taiwan.

I told them my UCLA team was better than the national team, and I would coach only if I could take my team. They agreed, and that was another free trip to play against international teams. If they were doing something we weren’t, I took note to improve our team.

Then the National Collegiate Athletic Association made a rule that we could only travel to a foreign country every four years. No other college teams in the United States, including basketball, were traveling abroad, so the rule was meant to stop us.

However, Puerto Rico is a commonwealth of the United States. So, for the next three years, I took my team to Puerto Rico to play their national team. There were no pro leagues, so the best players stayed in Puerto Rico, providing excellent competition.

We continually went to Western Europe every four years, the last time I won a championship before I retired was in 2006, I took my team to Italy. Where we played ten matches against players making, perhaps, a million dollars. And we found out we could compete with those teams, and we usually won after a foreign trip.

Coaching the U.S. team in 1971 and 1972 without a salary, I had to borrow money to coach the team, I told them I wouldn’t coach anymore and would focus on growing college volleyball. I didn’t return to coach the U.S. team until 1997.

In the meantime, I concentrated on UCLA, took my team around the world, learned from others, and used their best stuff.

That's what I did.

Instead of chasing every new trend, coaches today could maybe really take the time to try out their own ideas and see what actually works. It’s about not getting lost in the noise. How would you go about that?

Here's what happened. The first innovation I used was extremely quick sets in the 1960s. We set the middles as fast as they are getting set today. This was the 1960s, and nobody else was doing it.

Unless they commit blocked, which nobody did back then, they couldn't stop us. For years, this strategy was good enough for us to win because other teams couldn't practice against it and couldn't stop it when they saw us. Eventually, I had to innovate again because others caught up.

I'll tell you how that all happened. In 1969, we had a tryout, and I was teaching in Beverly Hills to afford coaching at UCLA. Our school newspaper had published we had a tryout that day.

When I walked into the gym, there were a hundred people there for the tryout, and I had only one assistant. We had to filter through all these people, and there was this little 5'7" Asian guy. I asked him what he did, and he said he was a setter. I gave him a volleyball and told him to jump set against the wall.

I got distracted and returned 15-20 minutes later. This kid was still jump setting against the wall. I told him he made the team and to come back. This player, Toshi Toyota, who was actually Korean, had transferred to UCLA from Japan, where he was a team captain and a setter. His dad took a Japanese name to get a job in Japan because Koreans weren’t hired there.

Toshi set the ball so quickly that I built a new offense around him. I had a middle attacker, Kirk Kilgour, who was left-handed. I had the players pass the ball to the left side when Kirk was in the front row so he could hit with his on-hand.

When Kirk was in the back, we passed to the right side for the right-handed quick attack. We ran gaps, back ones, front ones – everything nobody else had seen.

Usually, when we faced other teams, their middle blocker was still on the floor when we were hitting the ball. There was no video back then, so they didn’t get to see us until we played them.

We only started exchanging videos much later, in the 1990s.

I just took advantage of things I saw. Anything new was pretty good. When I played for the Hollywood Y in the 1960s, we tried to run a quick attack, but the coach was terrible. He spent about 20 minutes on it and then gave up. I was a middle hitter and left-handed, but everything was so slow. We were running sets that gave the middle attacker time to jump, get off the floor, and block.

In the United States, everything was slow until I started coaching at UCLA and sped it up.

Moving on to the third coaching fundamental, the "meritocratic approach," which emphasizes objective player evaluation and maintaining active competition. You maintained a professional distance from players, decisions were never personal but always about performance and team dynamics. What factors do you consider most important when deciding who deserves to play?

At UCLA, I initially had about eight players and didn't need assistant coaches. We'd often bring in players who were football or basketball athletes, but they hadn't played volleyball before. There was no high school volleyball; the only place volleyball was played was in college. Club teams existed, but only for adults, and volleyball courts were usually available at YMCAs or city gyms for a few hours a week, dominated by basketball players.