26. On the court: The Strength and Conditioning Experts.

We are back with the second part of this weeks 'On the court' series.

We sent out 3 questions about physical development in volleyball to 3 top experts in the field.

The questions were:

- Do you have a particular idea of how a volleyball athlete should physically prepare? Having different age groups in mind.

- What stages of physical preparation do you go through during the season. Total body preparation, specific strength,...?

- What do you think 17-20 year old athletes lack the most? And how would you improve that?

Vanny forwarded me the following document (he really went for it)...but as we were very interested in the performance tracking systems he mentioned we also had a long videocall last Monday evening to go over Vakifbank's data collection, best practices and day to day use of these numbers. Some screenshots of their worksheets with an explanation you can find at the bottom of this article.

Enter Vanny:

"Before talking about, discussing and analyzing the work needed for our young

promising volleyball players, we should monitor collect and analyze data that make us understand what really happens on a volleyball court, both during an official match(dictated by federal technical regulations), in a non complex game between friends and above all what happens in training.

With the current regulations the game of volleyball has undergone significant changes, the introduction of new rules and technology had a significant impact on the change in the conditional aspect of the sport itself.

The introduction of the 'Video Challenge', for example, inevitably conceded much longer breaks during high-level official matches both nationally and internationally.

The result is very clear: currently in an official volleyball match, active playing time is split up by long pauses. A recent study came to the obvious result that the 'time played' during a game is far inferior to 'no-play' time. In this regard the FIVB, which regulates our sport, is constantly looking for the winning formula, constantly making changes to the regulations, which can improve this aspect of the game and make volleyball more suitable to the needs of the viewer and the media.

Having said that, it is clear that "professional" volleyball is in some ways very "different" from youth volleyball, where the interruptions in the game seem be far less.

Since 7 years I am part of the technical staff of the Vakifbank Spor Volley Klub in Istanbul as responsible for the physical preparation of the elite team that plays in the top Turkish league and in the European Champions league.

I am fortunate to work in an environment completely dedicated to women's volleyball, from our mini volleyball teams (youngest teams) up to the elite team, the facility where we carry out our training sessions and official matches allows us to work at the highest level. We take advantage of all the most popular equipment, state-of-the-art monitoring systems including a Local Positioning System (LPS) which allows us to capture, archive and analyze every single movement of each single athlete in every single workout.

All this data has allowed us over the years to create our own database, every single player has a real time updated dataset.

The analysis and study of this data has allowed us to constantly monitor, control and modulate the workload to which the athlete is subjected during the course of their daily training and official matches.

The system uses chips that detect data in a fully covered network environment. It doesn't only monitors the jumping ability of the athlete but also the mechanical stress to which the athletes 'structure' (joints) gets subjected, plus the speed and direction of movement with the relative acceleration and deceleration data added to them. All this data is used to keep the training load under check.

Coming back to my own initial question, with all this data an important fact emerges: game time and training time have similar characteristics but there are different nuances at play.

So do we have to physically prepare for the training or for the game?

I still struggle to answer this question because I believe the real answer is somewhere in between...but personally I would abolish the obsessive study of the athletic in-game performance as the right answer, there is much more happening than just that.

What happens in a match hardly ever happens in training, not only from an emotional point of view but above all from a conditional point of view.

Let's go into detail and see what happens: 6 athletes share a playing field of only 81 square meters, the ball cannot be touched twice by the same player and can not be stopped. It's a quick game with a lot of variables that follow each other up at extreme speed and delivers a high mental load and asks for remarkable concentration.

And since we have no physical contact in our sport, technical excellence plays an even more important role.

Therefore the athletes will have to be prepared physically and mentally to release a quick and effective response when needed and in the meantime delivering varying but mostly very high outputs of strength and acceleration.

Execution and efficiency at game speed will represent the two main and essential qualities for an athlete in volleyball.

During the game, if we analyze what happens in an official match we will immediately notice the numerous breaks that follow each other up:

- very short actions, some not lasting more than 4-5 seconds

- very few actions per set over 15-20 seconds long (true, here we find a substantial difference between volleyball male and female)

- substitutions, time outs, video challenge requests, very often interrupt the

game -> favoring a decent recovery time between game actions.

All this means that data that we are used to use like following up the athletes Heart rate, VO2max and lactate have less significance.

Instead there is a new very significant data set to observe and that is the density and intensity of both the individual jumps AND the accelerations. The accumulated acceleration load.

The Accumulated Acceleration Load

This dataset provides the accumulated load of the player/athlete during the entire training session or game.

This metric adds up the differentials of accelerometer data in a single number, providing an overview of the load of the player produced by 3D-motion, jumps, impacts, etc. This metric is analogous to metabolic or conditioning work, but it is calculated from accelerometer data instead of position data.

So this dataset will tell us how intense the game or training was or was not. (more on how the Accumulated Acceleration Load is measured down below)

As an example.

Training session:

456,01 measured Accumulated Acceleration Load with 115,79 accelerations = a differential of 3,93

Game:

477,63 measured Accumulated Acceleration Load with 109 accelerations = a differential of 4,3

After all this we have deducted that the recovery of ATP and CP is fast, the oxygen debt is practically irrelevant and therefore, the work will be purely neuromuscular rather than metabolic!

(Volleybrains: not our goal to be a scientific journal here, but basic proficiency is good to have...this YouTube clip will give you a quick overview of ATP production in skeletal muscle, it's 4 min long, you'll need another 15 min to finish this entire article, do the work 🙂😉)

But what is happening in practice every single day?

In daily training, the coach requires a high number of repetitions of different

technical gestures of the players, in order to improve the various individual and team technical or tactical situations!

Therefore a large amount of jumps and accelerations will be performed daily to

be able to increase the amounts of contact with the ball and we try to reproduce the various technical tactical situations that could happen in the game. Mostly aiming for more than double the amount of these situations compared to a game.

Thereby in practice subjecting the musculoskeletal structure to a stress most of the times equal to double of what happens in a game.

In conclusion, as a physical trainer we should therefore be able to prepare our athletes to cope in the best possible way, to resist long and stressful workouts.

And to collaborate in the best way possible with our coaches to be able to moderate the load and intensity of work with the ball according to the daily, weekly, monthly and yearly requests.

So how do we measure the Accumulated Acceleration Load?

The Kinexon System has allowed us to learn a lot of what actually happens on the playing field. Again going back to the importance of not only the height and amount of jumping, but for sure and mostly the acceleration and deceleration of the athlete in the plain of our court and the loads accompanied by these loads.

The data that comes out of our continuous measuring highlighted a significant difference in terms of quantity and quality of accelerations between training time and matches.

One of the courtside RF antennas to enable precise position tracking. A lightweight (14gram) sensor is carried by the athletes between the shoulder blades to track the individual athlete.

What stages do we go through during the season?

With the current international calendar, in recent years I have not had the opportunity to program well in advance.

It is always necessary to adapt to the athlete's summer season where they are engaged with their national teams and competing internationally in various tournaments, plus the extra stress of being exposed (from next season once more)to a large amount of international travel so they arrive at the club conditioned in a certain way.

Working in a club with many players who play in their national teams makes it

practically impossible to program, as I have never had more than 3 max 4 athletes in pre season...consequently the programming gets continuously updated throughout the season.

In addition, each athlete comes back to us from a period of 4-5 months where they have used different methods, training styles and exercises by different S&C coaches.

So every year in October we are faced with the same situation: having to organize and modulate work that can meet the various individual needs of our athletes.

In a way we try not to change their acquired conditioning and performance habits too much. We try to merge their habits with our protocols.

We for sure also have to take care of the athlete's psycho-physical recovery and not change protocols 'to change protocols'. Of course this is also true for our technical volleyball coaches.

Better to prevent than to cure. More quality, less quantity.

At Vakifbank we have specifically structured the physical performance work to accommodate the development of our youngest female athletes in preparation for a possible and eventual spot in our 'first' team.

Our young volleyball players follow a path that will hopefully lead them to a future as an elite volleyball player.

From our youngest of age groups we try to create all the prerequisites for a young athlete to be able to eventually participate in training sessions with the first team without any noteworthy physical deficits. That is a huge goal, but we are structured in that way. Every coach of every age group is connected with each other.

Personally, I consider the Olympic lifts and all related exercises to be of considerable importance in our sport. From the youngest of age groups, but with respect to their growth curve, we teach the girls the correct techniques combined with a constant improvement of joint mobility.

So when and if the athlete is ready to join the first team the coach will be able to start a specific strength program from a solid foundation that was formed in the years before.

Vakifbank's and Turkish National team setter Cansu Özbay with a power clean at Vakifbank's gym

Personally I prefer to work a lot on quality rather than quantity.

I prefer that a young female athlete performs 1 repetition of a push-up correctly from a physiological point of view, instead of performing 10 push-ups performed in a bad way or even worse as a punishment in practice.

Those 10 badly executed pushups will only accentuate the imbalances already present as a result of technical movements that weren't established yet in the athlete's motor patterns.

So I would highly recommend to all the coaches of youth players to insist on correct execution and to completely stop shooting for a 'total number' of reps required.

Even today with our top athletes I prefer to put more attention to the continuous search for the correct execution technique with their personal maximum range of motion instead of paying attention to the weight that is lifted or the number of reps or sets.

Because of bad fundamentals, I have very often found myself with adult athletes that for that reason perform basic exercises in a completely wrong manner. All this starts a chain of compensation in the joint that in the long run inevitably leads to injury or if you're lucky 'just' to a functional overload.

All of this causing the time allotted for physical preparation to be diverted more towards the athlete's recovery than in the pursuit of maximum performance! And unfortunately that's exactly what happens today in many high-level clubs.

So why not take action now?

Why aren't our youth players taught to correctly perform a perfect squat or lunge with just their bodyweight? I am especially referring to the younger age groups. Why is the retraction and protraction of the shoulder blades not taught? Reduced scapular mobility is one of the main causes of professional volleyball players' shoulder pain and poor posture in general with young people.

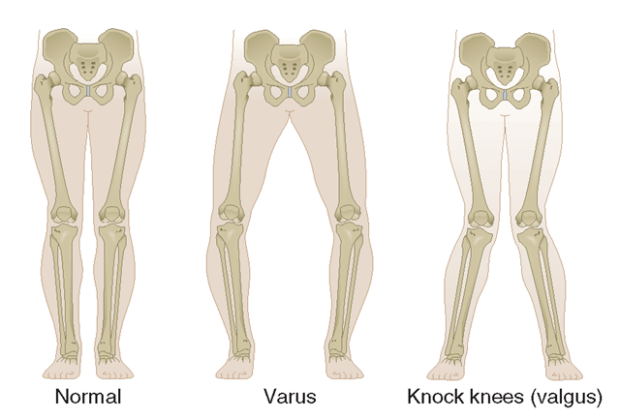

Why aren't adolescents taught to move the pelvis in all its planes? Kyphosis, hyperlordosis and limited mobility in the coxofemoral joint is one of the causes of varus and valgus in young adolescents and these are very common dysfunctions present in 80% of volleyball playing adults.

I strongly believe in physical work done with quality from a young age, because unfortunately, correcting a kyphosis or a varus in an athlete who is already an adult is very, very difficult.

So my advice to coaches helping out athletes in those late adolescent years (18-20yo) is to keep the quality up in the weight room, technical execution far outweighs stacking up the weight being used during the lift.

Nicola, do you have a particular idea of how a volleyball athlete should physically prepare?

I am one of those coaches who do not believe much in the variability of the stimulus. There are obviously many theories about it but I believe that evolution teaches us that it is the repetition of the stimulus that creates modifications to the homeostasis of our body.

Repetition of the stimulus means that if you want to achieve results on a physical level, you have to choose what the goal is and train it repetitively.

In my opinion, the physical (non-technical) goals to be sought for the volleyball athlete are maximal strength and mobility.

Maximal strength: with different methods and loads it the techniques can be taught immediately.

Teaching maximal strength means first of all having the technique to be able to lift loads, so the first step to train strength is not "loading" but "teaching the technique to load" and adapt the body to gradually increasing loads.

For example, often the limit in training the maximal strength for the legs is the weakness of the trunk. So before increasing the load for the legs you need to be sure that the trunk can support the weight, so it is necessary to strengthen the trunk even if we are talking about maximum strength for the legs.

Therefore, starting from the technique, even with only a wooden stick to do squats, without any load, we can begin to teach at 10yo already the correct technique to work on maximal strength in the future.

Obviously with low loads, many repetitions and long contraction times, in order to touch the first parameter necessary in the construction of the maximum force, we'll increase the foundation for all of that which is the resistant force.

Mobility: the various disciplines of gymnastics (artistic, rhythmic and all their deviations) teach us that mobility can be taught from a very young age.

Now, without having to start at 3 years of age to do the splits as they do in gymnastics in Eastern countries (they are among the best in the world), I think you should start working seriously on mobility from an early age, even before the age of 10. Because it is in that period that the best and most long-lasting results are obtained.

There are an infinite number of pathologies in professional and non-professional athletes of the knees, back, shoulders and hips that could be avoided with having good joint mobility, built at a young age.

A good range of motion at a young age allows you to learn both weightlifting and volleyball techniques better. Think of a lunge that a receiver makes in reception or a libero in defense: does it make a difference whether the mobility of the hip, ankle and hamstrings allows him to have the entire sole of the foot on the ground, or only the tip of the foot? Does it increase the athlete's overall stability? Anyone who has played knows...it matters a lot!

What stages do you go through during the season?

I don't believe in the periodization of loads in volleyball. In volleyball, and not only on the highest level, there are no "in season" periods where you can train heavy loads or unloads for prolonged periods.

The strength of a team lies in the ability to train together, with high quality, as many times as possible. Your physical work must allow this: be ready to train with as few physical problems as possible.

Volleyball is a technical sport, where the technical component dominates over the physical part. Many volleyball players are excellent players, but very bad athletes, sometimes fat, sometimes not very mobile, sometimes weak in terms of strength... but nevertheless excellent volleyball players.

In season in my opinion the load of physical work changes by + or - 20%, not a lot, based on the volume of training agreed with the head coach.

The discussion on injuries deserves a separate book 😊.

The concept is to try to maintain and improve strength levels, through exercises that don't increase the physical problems that of a lot of pro athletes have.

Let us remember that in the end, it is almost always the training with the ball that increases problems in the knees, shoulders and back. So in the weight room we try to solve (when possible) or just "put some band aids" (when not possible) on the chronic problems of each player.

What do you think 17-20 year old athletes lack the most? And how would you improve that?

Like I answered the first question ..Strength and mobility.

Power is certainly very important in a jumping sport like volleyball. So in the gym that needs to be trained, but with a lot of moderation. During the technical training the players already produce a huge amount of explosive force and maximum dynamic force ("Power") I do not think, in order to avoid overloads, that I have to train a lot even in the weight room.

So, I know this is getting boring, but, maximal strength and exercises with maximal range of motion to improve mobility.

A young player, if his body allows him to train, set, jump, attack, block and receive with quality, every day for 365 days a year, well that should be the goal.

He does not become a great player if he trains 182 days a year but can lift 300kg in squats. So my goal as a trainer is to make his physique strong enough to handle the technical workload.

Sebastiano, do you have a particular idea of how a volleyball athlete should physically prepare? Having different age groups in mind.

Working in a high-level environment like mine, everything goes to it's extremes, the more the athlete is evolved, the more their training must be specific. It's useless to let a marathon runner run the 100 meters to improve their sprinting in the last 100 meters of the marathon.🙂

I do not think there are precise periods to train the various and varied aspects of physical performance, all this depends very much on the individual characteristics of the individual athlete.

Having said that it is always a good idea to start from multifaceted disciplines for children from ages 7 to 12 and then start targeting more specifically.

In general I would say start building the right motor patterns, mobility and flexibility, increase the static strength and ultimately add on some explosive strength training at a later teenage age.

What stages do you go through during the season. Total body preparation, specific strength,...?

Always starting from the assumption that we are talking about professional athletes of the highest level, I have 2 main objectives.

The first is to maintain a good state of health and the second one, building on the first one, is to the increase specific strength required in volleyball, most importantly the explosive strength and fast strength resistance.

Evaluation and relying on objective data will be the key to understand if the work is done correctly, to simplify things I perform skinfold measurements and jump tests.

During season preparation, the work will focus more on the construction of a good physical condition which aims to minimize or eliminate various in season tendon discomforts and on functional overload. Gradually increasing the loads and the speed of execution of the movements.

All this must be tested, I use as you have seen in by "La Gazzetta dello Sport" the Vert system as a reference, but we also still use specific tests with the Vert.

What do you think 17-20 year old athletes lack the most? And how would you improve that?

This question is one to which I feel I can give an answer that will be generic and rather political even.

In Italy the real "center" for the development of motor skills of our children was the schooling system, nowadays everything is limited to the personal decision of parents to enrol their children in private sports centers, therefore this foundation, the development of motor skills has been lacking or highly dependent on choice and not because of our sports culture.

Movement and learning to move should start from being in nature, children should play outdoors, climb trees etc.

The few Italian volleyball talents that appear on the scene arrive ready and they were developed in private clubs or by our federations programs. I haven't been working in Italy in the previous decade so I believe I can't give a good answer on what is lacking the most in that age group.

In any case for young athletes, the main thing is to build a physical foundation that allows you to support the workloads of the future. A healthy body will be able to support the training dynamics of volleyball, which despite not being a contact sport, is an exhausting sport because we have an elevated repetition of the same technical gestures over and over again.

A big 🙏🏼 to Nicola, Sebastiano and Vanny for their cooperation.

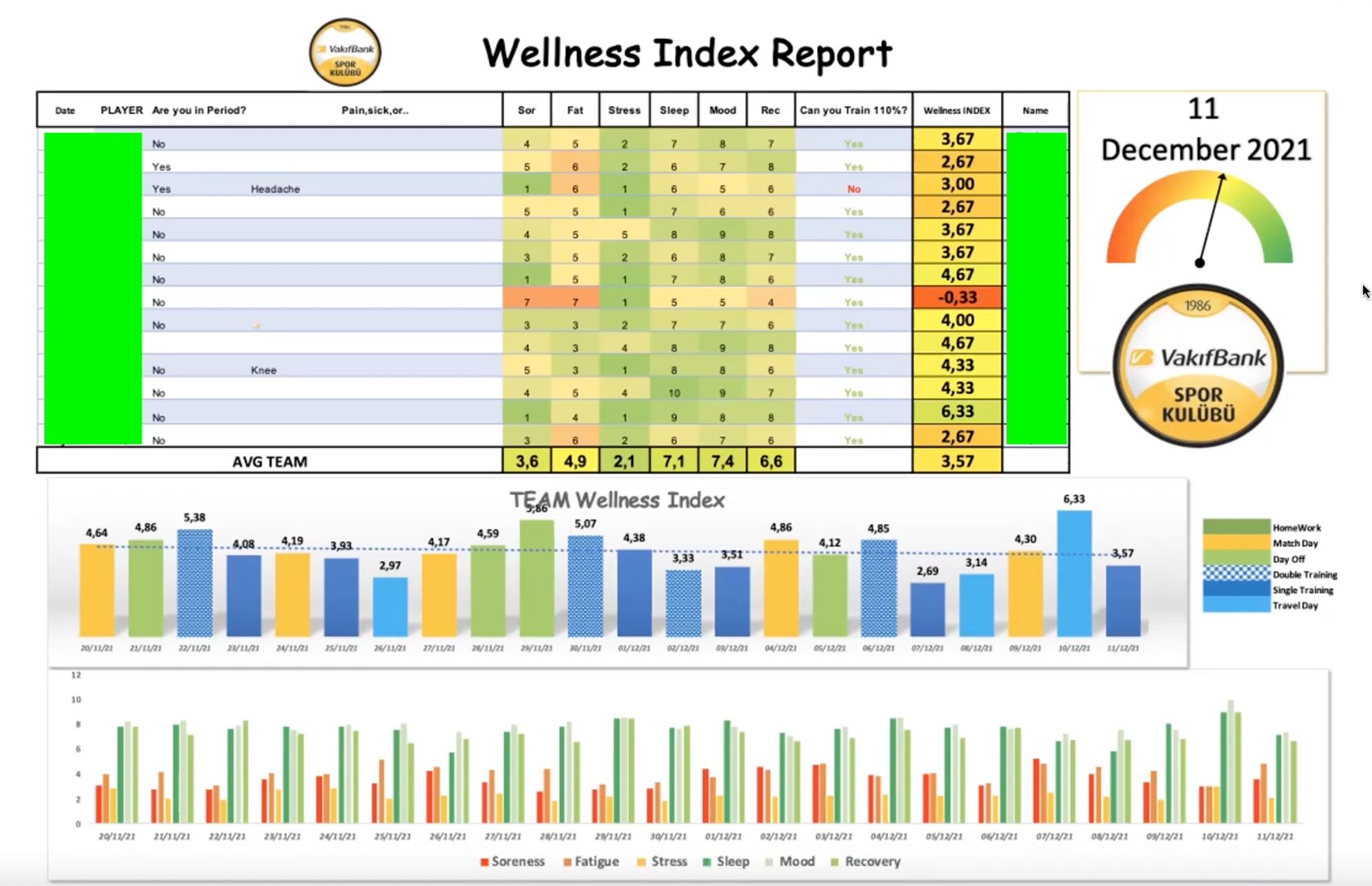

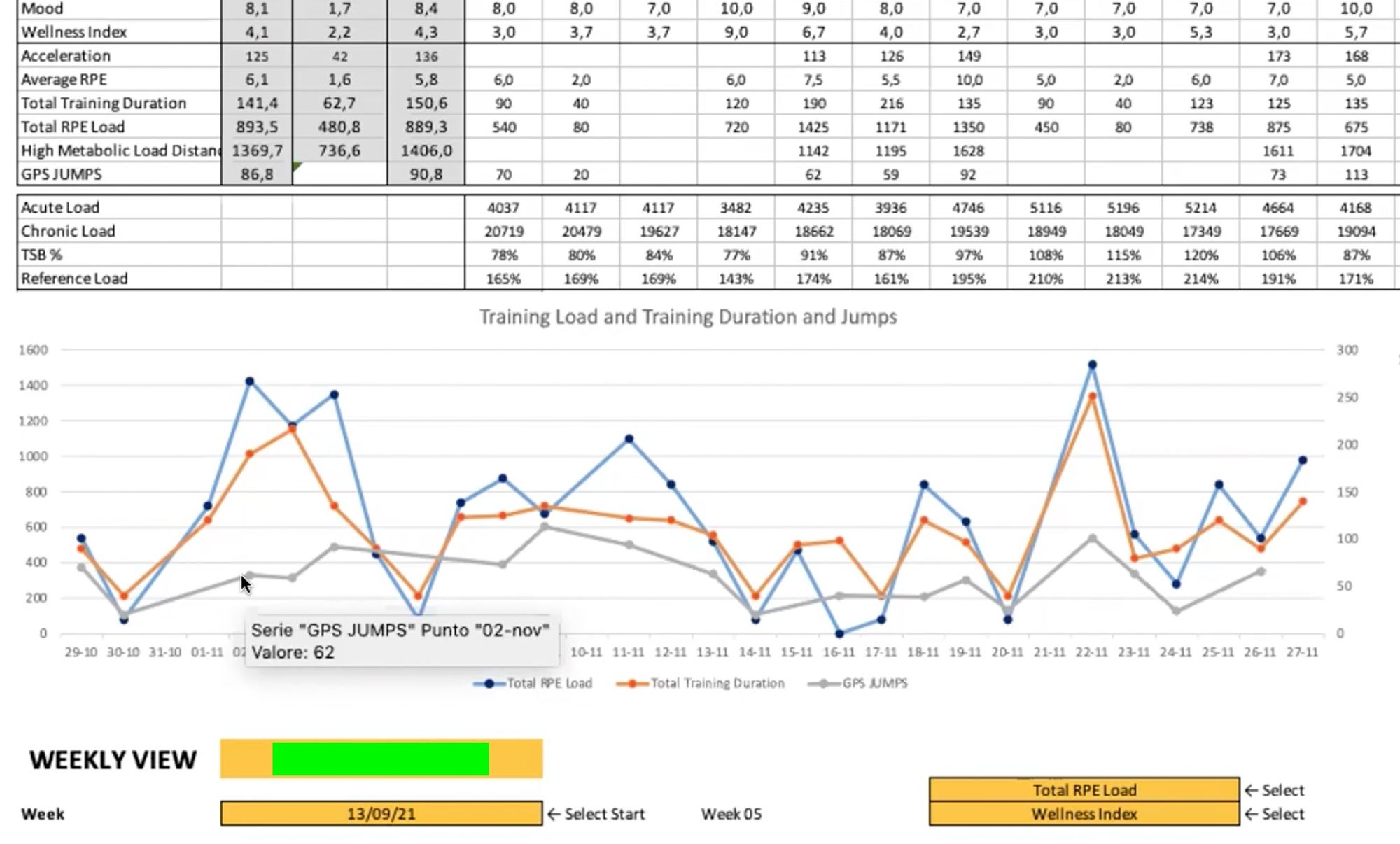

With every screenshot we'll add a short note at what you are looking at and what is important. For privacy reasons we blanked out the players names. (of course)

- Every morning the athletes fill in a Google form. They score their level of recuperation, mood, quality of sleep, soreness, fatigue and stress levels from 1-10. The spreadsheet fills itself up. Before the athletes hit the morning practice the coaching staff already has a sense of today's individual and team wellness score

- In the middle of the graph you can find the 'Team Wellness Index', the goal here is to arrive at an overall score around '4' on game days. (yellow is a game day)

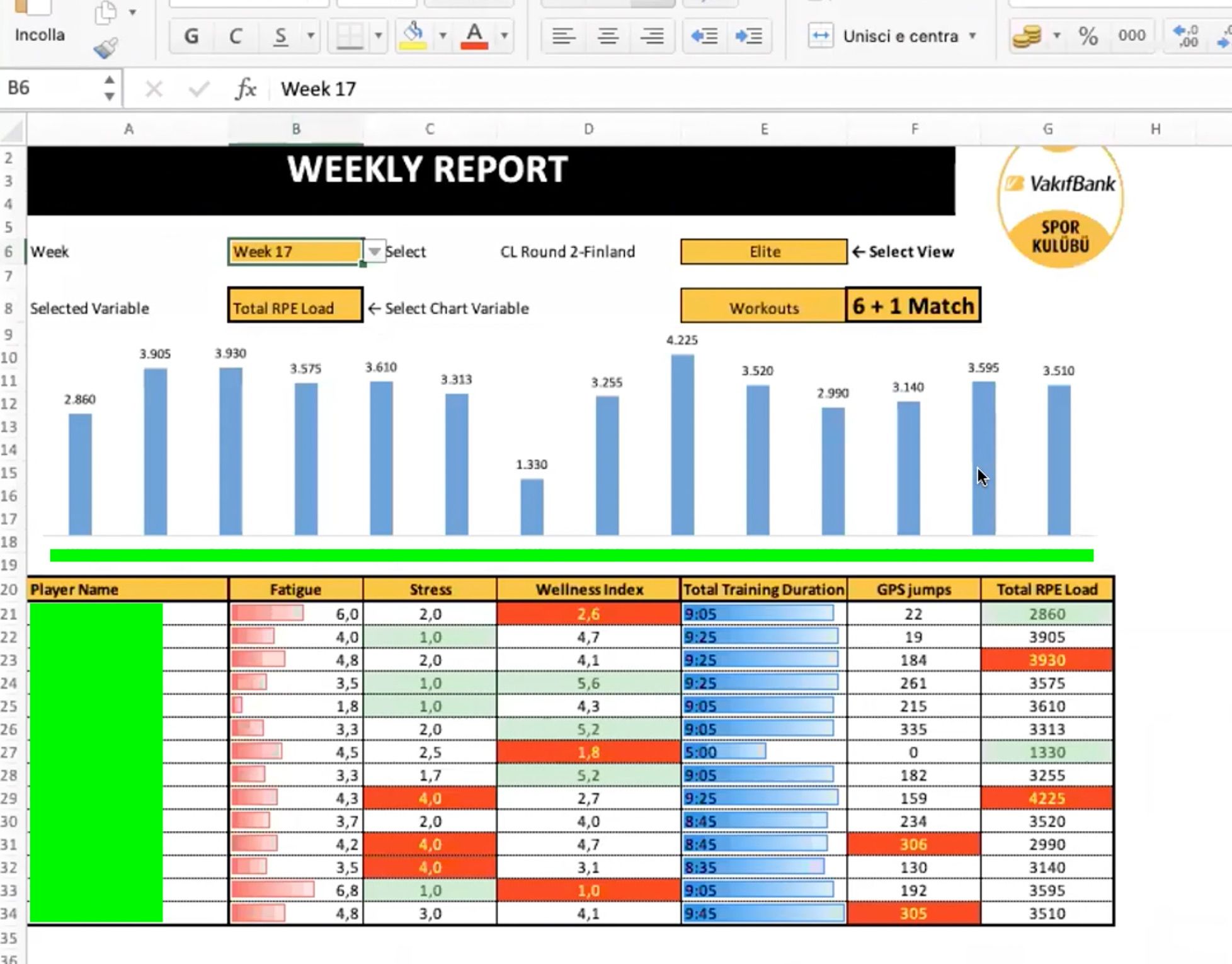

- General stats come together in this weekly report. We see the Total RPE load here also. This number gets calculated out of the aforementioned Accumulated Acceleration Load...we need to note that there is a conversion unit that gets used for every activity NOT being performed in the home gym of Vakifbank. (of course only the home gym has the proper network to measure the acceleration metrics)

- On the 3rd row you can see that this player has a total RPE load of 3930, even though they performed an average amount of jumps. Indeed, we're talking about a libero/ setter here...(not gonna show or tell 🙂)

- at the top of the graph that is visualised we can read 'Training load and Training Duration and Jumps'. You can find a decent amount of days with an average amount of jumps BUT with a high output of Total RPE Load. Going back to the point made by Vanny at the start of this post, charting the variations in acceleration and deceleration will get you closest to the actual training load/ output delivered by the athletes and that isn't always correlated to the amount of jumps.

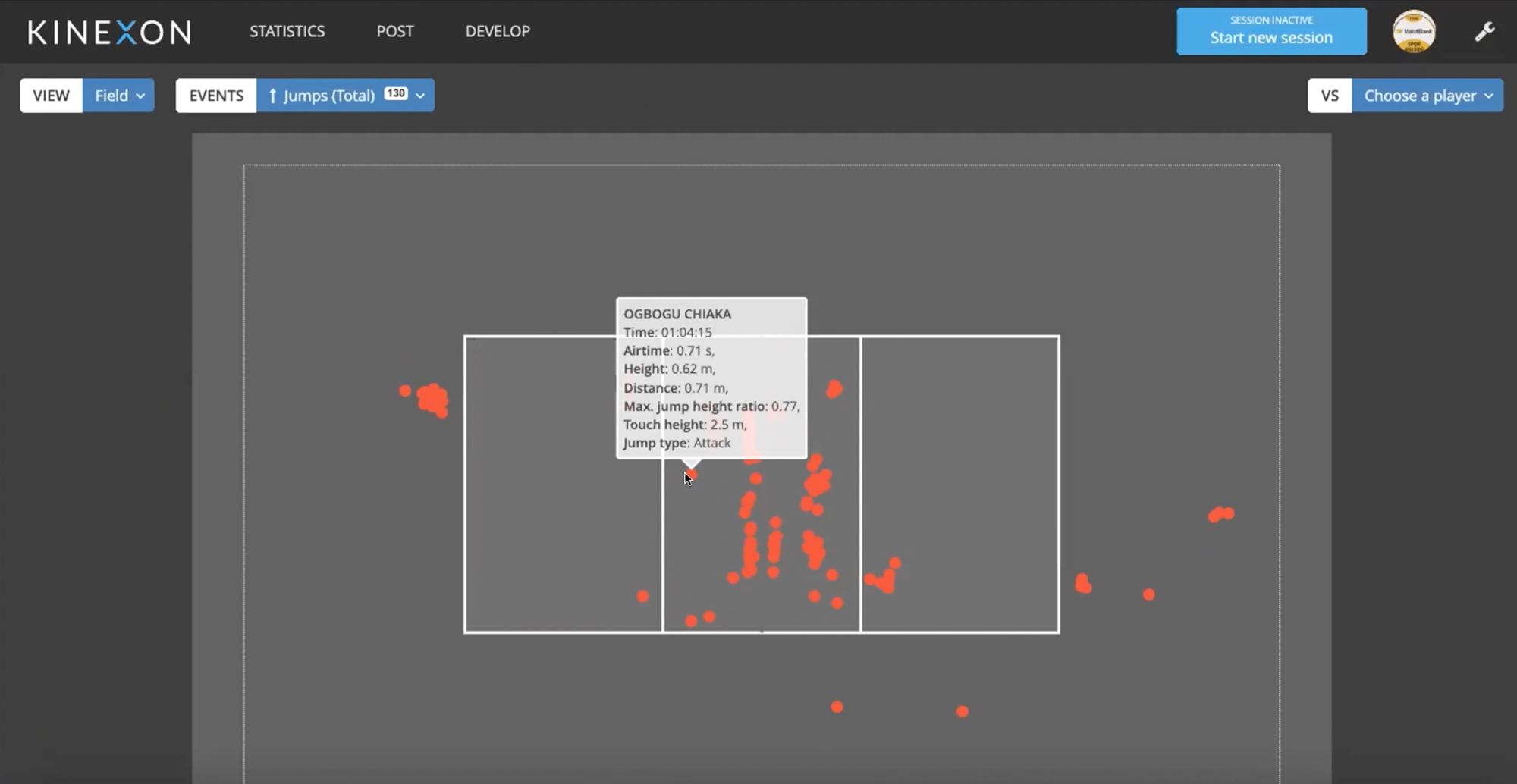

- Chiaka's jumps in that specific training session are charted here. X axis is the training time, Y is the height of the jump. We marked the event with a green ellipse. Under that selection tab you can select way more options, again acceleration etc...

- On this last slide you can see the same jumps as on the previous slide, but charted out on the court. There will be an update of this software next season. The 'touch height' will get accurate (you'll be able to add the standing reach of every single athlete, right now it measures your 'touch height' relative to your own height)

- Jumps can be filtered out here, same goes for accelerations, there is another screen with the movement in the plane of the court without the 3rd dimension etc.

To end; in our video call with Vanny we talked at length about the use cases for those acceleration and deceleration data sets.

And more importantly about the difference between both stats in the individual athlete. Most of the initial insights in how to use this data comes from the Juventus Lab (soccer) and they experienced a greater amount of injuries in athletes IF there was a big difference between both stats.

If there weren't issues with aches or other injuries (an athlete landing in an inefficient manner) mostly posterior work for the lower body was needed to decrease the difference between the acceleration and deceleration stat and therefore decreasing the occurrence of injury.

Enjoy your day.🙂